KING ARTHUR and HIS KNIGHTS

FACT OR FICTION?

(Investigator 211, 2023 July)

FACT OR FICTION?

(Investigator 211, 2023 July)

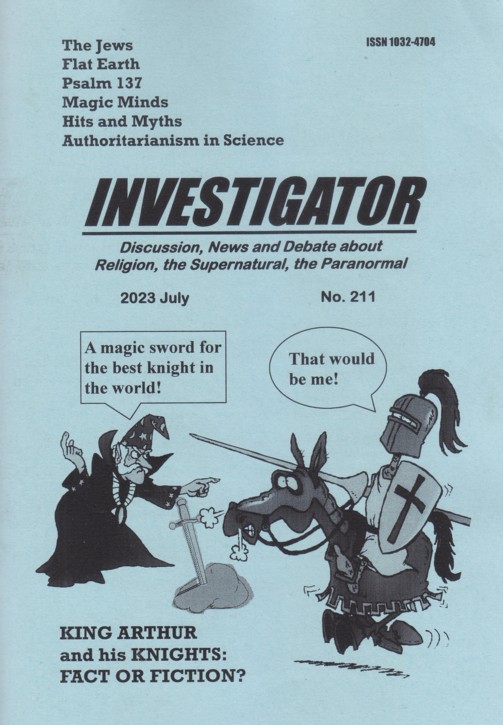

This image: From IMSI's MasterClips/MasterPhotos 202,000 © 1997 Collection,

1895 Francisco Blvd. East, San Rafael, CA 94901-5506, USA

1895 Francisco Blvd. East, San Rafael, CA 94901-5506, USA

THE STORY

Camelot in King Arthur's kingdom of Logres was, according to legend, a walled city with a castle surrounded by open spaces used for tournaments and close to a major river. Camelot was England's main centre of power in the 6th century; the place of Arthur's birth; and the location of the round table where he feasted with his knights.

When I was ten the 15-chapter serial The Adventures of Sir Galahad played at the local cinema. The following Christmas I received the novel King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. It was a 1950s edition but similar to Briggs (1922) which I'll refer to in this article.

As a kid I was enthralled at:

• Arthur and Galahad each pulling a sword out of a boulder;

• Another sword, "Excalibur" miraculously received from the "Lady of the Lake";

• Arthur's greatest battle;

• The Knights of the Round Table, their jousts and adventures;

• Sir Launcelot — "the greatest fighter in the world";

• Queen Guinevere's scheduled execution and Launcelot charging to the rescue;

• The "Quest for the Holy Grail", and plenty more.

• Another sword, "Excalibur" miraculously received from the "Lady of the Lake";

• Arthur's greatest battle;

• The Knights of the Round Table, their jousts and adventures;

• Sir Launcelot — "the greatest fighter in the world";

• Queen Guinevere's scheduled execution and Launcelot charging to the rescue;

• The "Quest for the Holy Grail", and plenty more.

Is any of it real history?

ASSESSMENT 1935

The assessment of the historicity of King Arthur has changed little since1935 when we read:

|

To what extent King

Arthur was an historical personage is a question of curiously little

importance, and is likely toremain unanswered. What is important is

that this legendary British chieftain is the nucleus around which has

grownup the romantic cycle of legend associated with his name and

those of his knights : legends in which there is plainly some

substratum of historical fact, but which have been so intermingled with

and enriched by elements of the older Celtic mythology, that the task

of analysing the fact and the myth in them is of interest only to a few

enthusiastic researchers. The earliest mention of King Arthur is by

Nennius (q.v.) in his History; and the cycle of legends concerning

Arthur and the Round Table developed through the work of Geoffrey of

Monmouth, Wace, and Layamon, and the prose romances of such writers as

Chretien de Troyes. There has been a sharp division of opinion as to

whether the main origin of these legends lies in Brittany or in Wales,

and there is plenty of substance for each theory.

(The Modern World

Encyclopedia, 1935) |

BRITAIN AFTER ROME

In the 5th century the Western Roman Empire was dying.

In 410 CE Rome was sacked by Visigoths and its legions left England.

Several expeditions sponsored by clerics crossed from France to help

Christians against "heathens". But after 455 CE when Rome was again

pillaged communication with Britain was tenuous.

Until recently it was believed that civilization in Britain died, primitive living returned, no uniform law existed, warlords battled each other, and into this lawlessness, adding to it, came Saxons from Germany.

These conditions and the collapse of the papyrus trade made British history for the next three centuries fragmentary. Papyrus decays in wet climates and documents written on it had to be re-copied every half-century. Velum and parchment last longer but were expensive.

The breakdown, however, was not total. A Roman-British military leader named Riothamus was active around 470CE and twice crossed the Channel to fight the Goths. After 500CE another local hero name Artorius won significant victories.

Until recently it was believed that civilization in Britain died, primitive living returned, no uniform law existed, warlords battled each other, and into this lawlessness, adding to it, came Saxons from Germany.

These conditions and the collapse of the papyrus trade made British history for the next three centuries fragmentary. Papyrus decays in wet climates and documents written on it had to be re-copied every half-century. Velum and parchment last longer but were expensive.

The breakdown, however, was not total. A Roman-British military leader named Riothamus was active around 470CE and twice crossed the Channel to fight the Goths. After 500CE another local hero name Artorius won significant victories.

KNIGHTS, ARMOUR and CHIVALRY

Arthur's knights clad in armour and jousting is anachronistic.

The head-to-foot plate-armour, which is attributed to Arthur's knights

(including in Briggs' novel) was introduced in the 15th century (but

became militarily obsolete as gun-technology improved).

Rome had mounted nobles, and Gothic invaders of its Empire included cavalry. "Cataphracts" were mounted warriors clad in protective mail, and were known across Asia and Europe from before 1000 BCE until the 15th century CE. In the 14th century "knights" were a European social class of whom many were still mail-clad mounted warriors but the real knights had the heavier plate-armour.

Some commentators claim that armour was so heavy that knights were lifted onto their horses with cranes and that unhorsed knights were therefore helpless. However, the weight of head-to-foot-armour was about 25 kilos, light enough for a man to stand up after falling. Nevertheless, after knights unhorsed each other with lances they could not have pranced in sword-fight for hours — a common scenario in Briggs — with 25 kilos on them! When Sir Launcelot encounters Sir Turquine (who had defeated and imprisoned 60 knights of the Round Table) we read:

Rome had mounted nobles, and Gothic invaders of its Empire included cavalry. "Cataphracts" were mounted warriors clad in protective mail, and were known across Asia and Europe from before 1000 BCE until the 15th century CE. In the 14th century "knights" were a European social class of whom many were still mail-clad mounted warriors but the real knights had the heavier plate-armour.

Some commentators claim that armour was so heavy that knights were lifted onto their horses with cranes and that unhorsed knights were therefore helpless. However, the weight of head-to-foot-armour was about 25 kilos, light enough for a man to stand up after falling. Nevertheless, after knights unhorsed each other with lances they could not have pranced in sword-fight for hours — a common scenario in Briggs — with 25 kilos on them! When Sir Launcelot encounters Sir Turquine (who had defeated and imprisoned 60 knights of the Round Table) we read:

…for both their horses

were killed with the shock of that meeting and both men were flung from

their saddles. But they leaped up again lightly and began to fight with

swords. For two hours they fought,

round and round, till the grass was trampled and reddened… (Briggs pp 51-53)

round and round, till the grass was trampled and reddened… (Briggs pp 51-53)

Try it yourself. Lift 25 kilos, perhaps a sack of potatoes in the

supermarket, "leap up lightly" with it, then prance around, not for two

hours but a few minutes. It's unrealistic. Arthur's knights as

less-heavily clad cataphracts, however, remains a possibility and one

novel I've read is based on that idea.

The ideals of chivalry, chastity and knightly honour were added to the Arthurian legend by French writers in the 14th century. In the 19th century Alfred Tennyson's poem Idylls of the King (1859) depicts Arthur's knights as champions of Victorian morals, and Camelot, in Lady of Shallot (1832), as a virtual paradise. In the 5th century the real Britain was a lawless place of waring fiefdoms and invading Saxons. But that's not necessarily contradictory — both could be true because the legend is about an oasis of security when civilization disintegrated:

The ideals of chivalry, chastity and knightly honour were added to the Arthurian legend by French writers in the 14th century. In the 19th century Alfred Tennyson's poem Idylls of the King (1859) depicts Arthur's knights as champions of Victorian morals, and Camelot, in Lady of Shallot (1832), as a virtual paradise. In the 5th century the real Britain was a lawless place of waring fiefdoms and invading Saxons. But that's not necessarily contradictory — both could be true because the legend is about an oasis of security when civilization disintegrated:

Then King Arthur stood

up and made a pronouncement to them all, charging them from that day on

to

flee from treason and lies, to do no murder, to refrain from all wickedness and cruelty, to give mercy to

all who begged for it, to hold all womenkind in highest honour, and to fight to the death for them; never

to fight in an evil cause nor for gain of money or goods. "My knights shall be known in all future times

as the patterns of chivalry," he cried, and his tones rang down the halls of Camelot. (Briggs 1922, p. 36)

flee from treason and lies, to do no murder, to refrain from all wickedness and cruelty, to give mercy to

all who begged for it, to hold all womenkind in highest honour, and to fight to the death for them; never

to fight in an evil cause nor for gain of money or goods. "My knights shall be known in all future times

as the patterns of chivalry," he cried, and his tones rang down the halls of Camelot. (Briggs 1922, p. 36)

SOURCES

The only surviving British document from the Saxon-invasion era is by Celtic monk Gildas (died c.570). Gildas wrote the polemic Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae

(On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain) and mentions a hero, Ambrosius

Aurelianus who successfully resisted the Saxons, and a victory at Mons

Badonicus (Badon Hill) which later writers attributed to Arthur. But

Gildas does not mention the name "Arthur".

Welsh historian Nennius: "between 796 and about 830 compiled or revised the Historia Brittonum,

a miscellaneous collection of historical and topographical information

including a description of the inhabitants and invaders of Britain…"

(Encyclopedia Britannica) Nennius is the first to mention Arthur by

name and lists 12 battles from Welsh folklore, and the Badon Hill

battle, which Arthur allegedly fought. The story spread to Europe in

the 11th century when the Normans conquered England.

A famous Welsh reference to Arthur is in the song-collection known as Y Gododdin (The Gododdin) attributed to 6th-century poet Aneirin. One stanza praises a warrior who slew 300 enemies, but adds "he was no Arthur" — implying Arthur's martial skills were greater. However, Y Gododdin is known only from a 13th-century manuscript, therefore the passage could be a later interpolation. Poems attributed to 6th-century poet Taliesin, also mention Arthur, but are now believed to date between the 8th and 12th century. They include "The Chair of the Prince" which mentions "Arthur the Blessed" and "The Elegy of Uther Pendragon [Arthur's father]".

Annales Cambriae (Welsh Annals) is a compendium of Latin chronicles put together around 950 CE which list events in Wales, England, Scotland and Ireland and include two entries on Arthur. One mentions Badon Hill and dates it 516 CE, the other the Battle of Camlann in 537 where Arthur and Mordred (his son) killed each other.

In History of the King's of Britain (c. 1136) Geoffrey of Monmouth gathered scattered comments, Welsh folklore and perhaps an earlier manuscript and expanded these into a detailed review of Arthur's life. Geoffrey mentions Arthur's father Uther Pendragon, Arthur's conception at Tintagel (not Camelot) located on cliffs on the coast of Cornwall, the wizard Merlin, the sword Caliburn (later Excalibur), the knights, various adventures, battles with Picts and Scots, Arthur's conquest of Denmark, Norway and Gaul where Arthur wins a gigantic battle against Roman emperor Lucius Tiberius; and the final battle at Camlann against Mordred. Guinevere, Lancelot and Galahad are absent.

William of Malmesbury (1095-1143), a monk at Malmesbury Abbey, was Britain's main historian in the 12th century. Together with Abbott Godfrey he established a library of 400 works by 200 authors and himself wrote Gesta Regum Anglorum (Deeds of the English Kings) covering 449 to 1127 CE. William mentions Arthur briefly and considered him historical.

French poet Chretien de Troyes (1160-1191), sometimes called "the inventor of the modern novel", added more myth to Arthur than most others. He briefly mentioned Camelot, invented the characters Sir Lancelot (and the romance with Queen Guinevere), Sir Percival, Sir Gawain, and introduced the search for the Holy Grail, a vessel containing drops of Christ's blood, brought to England by Joseph of Arimathea. This was expanded into the "quest for the holy grail" which scattered Arthur's knights and started the decline of his kingdom.

Other French writers and storytellers elaborated Camelot with imaginative details and additional knights, and painters portrayed the main characters and events on canvas.

A famous Welsh reference to Arthur is in the song-collection known as Y Gododdin (The Gododdin) attributed to 6th-century poet Aneirin. One stanza praises a warrior who slew 300 enemies, but adds "he was no Arthur" — implying Arthur's martial skills were greater. However, Y Gododdin is known only from a 13th-century manuscript, therefore the passage could be a later interpolation. Poems attributed to 6th-century poet Taliesin, also mention Arthur, but are now believed to date between the 8th and 12th century. They include "The Chair of the Prince" which mentions "Arthur the Blessed" and "The Elegy of Uther Pendragon [Arthur's father]".

Annales Cambriae (Welsh Annals) is a compendium of Latin chronicles put together around 950 CE which list events in Wales, England, Scotland and Ireland and include two entries on Arthur. One mentions Badon Hill and dates it 516 CE, the other the Battle of Camlann in 537 where Arthur and Mordred (his son) killed each other.

In History of the King's of Britain (c. 1136) Geoffrey of Monmouth gathered scattered comments, Welsh folklore and perhaps an earlier manuscript and expanded these into a detailed review of Arthur's life. Geoffrey mentions Arthur's father Uther Pendragon, Arthur's conception at Tintagel (not Camelot) located on cliffs on the coast of Cornwall, the wizard Merlin, the sword Caliburn (later Excalibur), the knights, various adventures, battles with Picts and Scots, Arthur's conquest of Denmark, Norway and Gaul where Arthur wins a gigantic battle against Roman emperor Lucius Tiberius; and the final battle at Camlann against Mordred. Guinevere, Lancelot and Galahad are absent.

William of Malmesbury (1095-1143), a monk at Malmesbury Abbey, was Britain's main historian in the 12th century. Together with Abbott Godfrey he established a library of 400 works by 200 authors and himself wrote Gesta Regum Anglorum (Deeds of the English Kings) covering 449 to 1127 CE. William mentions Arthur briefly and considered him historical.

French poet Chretien de Troyes (1160-1191), sometimes called "the inventor of the modern novel", added more myth to Arthur than most others. He briefly mentioned Camelot, invented the characters Sir Lancelot (and the romance with Queen Guinevere), Sir Percival, Sir Gawain, and introduced the search for the Holy Grail, a vessel containing drops of Christ's blood, brought to England by Joseph of Arimathea. This was expanded into the "quest for the holy grail" which scattered Arthur's knights and started the decline of his kingdom.

Other French writers and storytellers elaborated Camelot with imaginative details and additional knights, and painters portrayed the main characters and events on canvas.

The Vulgate Cycle (or

Lancelot-Grail Cycle) is a 13th-century (c.1220), five-volume,

2000-page compilation of French stories of unknown authorship which

retell the Arthur legends, expand Chretien de Troyes' narratives, focus

on Lancelot and Guinevere, and include hundreds of additional

characters. Arthur's England is portrayed as a land of knights,

jousting tournaments, adventure, romance, magic, dragons, giants and

super-human heroes. The kingdom is named Logres, Camelot was within

sight of the ocean and surrounded by meadows. Queen Guinevere played

chess, the Holy Grail quest began 453 years after Christ's

resurrection, the Round Table was a wedding gift from Guinevere's

father and seated 150 knights, Arthur and his son Mordred at the end

kill each other, and afterwards Camelot is destroyed by an invasion

from Cornwall led by a "King Mark".

The Post-Vulgate Cycle (c.1230), a shorter re-write of the Vulgate Cycle, sidelines the Lancelot-Guinevere love entanglement and devotes more space to the Quest for the Holy Grail.

In the 15th century Le Morte d'Arthur (The Death of Arthur) by Sir Thomas Malory (c.1400-1470) drew heavily on the French Vulgate cycles and retold the entire legend in a single work intended to be comprehensive and authoritative. The Death of Arthur was one of the first books published by English printer William Caxton in 1485. Therefore in England and its colonies the Arthurian legends are best known from Malory's book. Malory got the date approximately correct, the 5th century, but the society he describes is 15th century. Malory's work in turn influenced Alfred Tennyson, T.H. White, John Steinbeck, Mark Twain and others who reinterpreted the legends. Malory's Arthur is what most subsequent English Arthur-novels (including Briggs 1922) and 20th century Arthur-movies are adapted from.

Briggs calls Lancelot "Launcelot", Tristan "Tristram", and does not identify Mordred as Arthur's son nor Galahad as Launcelot's son besides other differences.

A large literature about Arthur's knights accrued over a period of centuries in Wales, England and France, the stories inconsistent with one another, and virtually all of it myth.

Consider the number of knights. Wikipedia says:

The same Wikipedia page lists by name 57 "notable knights", and another 78 "less prominent knights" mentioned in the "Winchester Manuscript of Le Morte d'Arthur". Several names are names of real 15th century knights but don't appear in earlier historical manuscripts.

Briggs' novel mentions about 25 knights by name but: "One hundred and fifty knights can sit about it [the Round Table] any one time..." Two successive seats to one side of Launcelot remained free. After Percivale and Galahad arrived: "they sat at supper that night, with all the five score and fifty sieges [seats] filled..." (p. 132)

When the Romans departed around 410 CE Picts and Scots soon raided all over Celtic Britain.

A ruler in south England, requested the Jutes, a Germanic tribe in Denmark, for assistance. They assisted, but then stayed, and proceeded to subjugate the native British. Germanic tribes — Old Saxons, Angles and Jutes — arrived in force and plundered, enslaved and slaughtered.

The invaders preferred to build new communities in cleared forest areas and the Roman towns declined.

Britain's many warlords and petty kingdoms acknowledged one or a few powerful rulers as a "Vortigern" or overlord. One overlord was Ambrosius Aurelianus, a man with Christian beliefs and Roman background. Two German brothers, Hengist and Horsa, may have served him as mercenaries before turning against him.

Ambrosius' son born about 475 CE was Artorius, a Roman name derived from the family's allegiance to Rome. We see a possible derivation of "Arthur" from "Artorius". However, in the Arthurian legend Arthur's father is not named Ambrosius but Uther Pendragon.

Around 500 CE Saxon incursions became a mass migration. They came in boats, similar to the future Viking-boats, about 20 metres long, powered by rowing.

When Ambrosius died Artorius fought successful battles against Picts and Scots in the north and Saxons in southern England. The culmination was the battle of Badon Hill in 516 CE in which Artorius demolished a Saxon army according to the writer Nennius.

Briggs doesn't mention Badon Hill, instead describes an invasion of Flanders by Arthur with 62,000 men, where he defeats Lucius the Roman Emperor. (pp 37-42)

Briggs describes preparation for the battle: "The bowmen went into the fields and set up their targets and they shot from sunrise to star-rise till the meanest of them could shoot a second arrow upon a first and split it from feather to head." (p. 39) The Mythbusters (Episode 36) tried to replicate such splitting of arrows and found it impossible with solid wood arrows: "Because the second arrow will follow the grain, which will lead to the side before it makes it to the end." Success has only occurred, still extremely rarely, when the first arrow was made of hollow bamboo or modern carbon fibre. This is an incidental example of how myth gets built upon previous myth.

The "great battle" itself is also fantasy. In the 6th century neither Rome nor the British had the sort of military power and political influence described.

The Baden Hill battle in 516 CE, if it happened — some scholars now query that too — was not a battle of armour-clad knights on horses or even of cataphracts. Saxons might ride to a battle area on horses but fought on foot with swords, spears and battle axes and protected by a helmet, shield and leather jacket.

Artorius' victories resulted in Saxons vacating south-west England and established him as the dominant king. Twenty years later, round 537 CE, his kingdom collapsed in civil war. The writer Gildas describes this period but writes more propaganda than history and mentions neither Arthur nor Artorius by name.

Arthur died, according to tradition, after a long separation from Guinevere, when he tried to visit her at Glastonbury where she lived in a convent. In Briggs' book Arthur and Mordred kill each other in a final battle.

In the mid 6th century the Arthurian or Artorius peace, if it happened, was gone. The Anglo-Saxons dominated England and set up seven kingdoms, the Heptarchy:

These kingdoms fought each other until around 850 CE the seven became three. At this time came the reign of Alfred the Great, King of Wessex, and the Viking invasions.

The subjugated British in the 7th to 9th centuries perhaps got comfort from legends based on Artorius, now attributed to Arthur, to which Alfred's struggles perhaps provided further material.

Briggs writes:

Sir Tristram of Ireland was his equal:

And, later, Galahad: "No man could stand against him when the jousting began, save only two, Sir Launcelot and Sir Percivale." (p. 132)

Percivale arrived in Camelot after Tristram returned to Ireland and got the second of the two vacant seats next to Launcelot. (p. 122)

Camelot appears in detail in the Vulgate Cycle, the c.1220 French compilation mentioned above. Geoffrey of Monmouth implied Tintagel, on the Cornwall coast, was Camelot and Arthur its king; and Alfred Tennyson advocates Tintagel in his poem Idylls of the King.

Archaeologists have excavated the remains of large 6th century buildings at Tintagel and unearthed high-standard imported pottery, indicating the inhabitants were upper-class. Skeletons dug up in southern England have undergone genetic analysis. The findings suggest that in the sixth century Saxons dominated eastern England and traded with northern Europe. The British dominated the west and traded with the Byzantine Empire.

The two areas were apparently at peace for a time when Saxon arrival was by immigration not invasion. Tintagel was the main trading centre in the west and controlled locally-mined tin which was in demand in Europe to make bronze. Tintagel was prosperous but whether its king was Arthur is unconfirmed.

The "Arthur stone", discovered in 1998 in the ruins of Tintagel Castle, created a stir and featured in a TV documentary, but proved irrelevant.

During the 12th century, Arthur's character began to be marginalised by stories about Tristan, Lancelot, Guinevere, Percival, Galahad, Gawain, the Holy Grail, Merlin, and others.

The Welsh and French stories include hundreds of characters in thousands of pages, all even less historical than Arthur.

Arthur himself changes significantly:

The tales are largely of courtly love and knightly adventures with Arthur's reign as background. Lancelot, Guinevere and Galahad became important characters, Merlin's role greatly expands, Mordred is born from incest between Arthur and his sister, and Camelot becomes Arthur's capital.

Galahad was the illegitimate son of Lancelot and Lady Elaine. Elaine's father, King Pelles, purchased a magic ring from an "enchantress" that makes Elaine look like Guinevere and fools Lancelot into spending the night with her. Galahad first appears in the fourth book of the Vulgate Cycle and continues in the Post-Vulgate Cycle and Malory's The Death of Arthur. Galahad is raised by a great aunt in a nunnery. Arthur, upon realizing Galahad's greatness, leads him to a river on which floats a stone with a magic sword embedded, inscribed: "Never shall man take me hence but only … the best knight of the world." Galahad becomes renowned for his gallantry and purity. He banishes demons, performs miracles, and finds the Holy Grail.

A huge amount of literature is about Merlin featuring many stories inconsistent with each other. His traditional biography casts him as sired by an incubus or lustful demon from whom he inherits supernatural powers including prophecy and shape-shifting. Merlin was created by Geoffrey of Monmouth probably as a composite figure based on previous kings, madmen, seers and prophets. Merlin became popular in Wales and was later rounded out by writers in France. One manuscript has him as the builder, helped by giants, of Stonehenge.

The popularity of Arthur stories gradually declined after 1634 when reprinting of Malory's The Death of Arthur stopped. Interest reawakened in the 19th century after its reprinting recommenced in 1816, and William Wordsworth wrote The Egyptian Maid (1835), and Alfred Tennyson's poem The Lady of Shallot (1832) gave an enchanting description of Camelot.

In the 19th-20th centuries came many retellings of Arthur in novels, most of them abridged or adapted from Mallory, including:

King Arthur by British novelist Phyllis Briggs (1904-1981) achieved many editions by different publishers in the 1950s and beyond. The existence of the 1922 version when she would have been only 18 is an anomaly.

Briggs includes miracle-stories like the names of knights appearing miraculously on their round-table seats, and the "lady of the lake", but sanitises out most of the medieval stories of the supernatural and magic and monsters.

There were British leaders who defended Britain against Saxon invaders around 500 CE. But Arthur is not mentioned in any surviving manuscript written between 400 and 820.

The Ecclesiastical History of the English People (731CE) by Anglo-Saxon historian the Venerable Bede (673-735) mentions the Badon battle but not Arthur.

Archaeology has not discovered the Round Table, Excalibur, the Holy Grail, or 6th-century plate-armour; or identified Camelot, Arthur's castle, or Avalon (the island with Arthur's tomb); or found his other tomb in the ruins of Glastonbury Abbey. Nothing.

To a sparse history of a violent 6th century England and a local hero name Artorius, story-tellers and poets, beginning three centuries later, added ever more characters, adventures, miracles and supernatural events.

And that's what we have — imaginative romances and miracle-stories, mutually inconsistent, authored as entertainment which, by shear repetition, got accepted as history. The most useless presentations are the movies since these re-adapt mythical adventures themselves based on earlier myth. Guinevere, clad in only a leather, two-piece, beach costume, certainly did not sword-fight in battles as does Keira Knightley in Arthur (2004).

In the 20th century, historians such as John Morris in The Age of Arthur (1973) still regarded Arthur's reign as probable. Others have tried to connect Arthur with Scotland, or to legends originating in the Ural Mountains. The modern fiction and research on Arthur amounts to a vast literature exceeding the Medieval material. But most historians now regard Arthur as unhistorical, no more factual than Galahad, Lancelot, Merlin or the Lady of the Lake. Some regard even Aurelianus, Artorius and Hengist and Horsa as myth — concluding that the ancient historians who mention them relied on hearsay.

Feerick (2021) quotes British archaeologist Nowell Myres (1902-1989) who devoted 50 years to the search for Arthur: "no figure on the borderline of history and mythology has wasted more of the historian's time."

To prove that something never existed can be difficult because in some unexplored corner it perhaps did. Absence of evidence is not always evidence of absence. On present evidence, however, Arthur and his knights are no more historical than Spiderman or Wonder Woman.

Ardrey, A. 2013 Finding Arthur: The Truth Behind the Legend of the Once and Future King, Duckworth

Ashe, G. 1906 From Caesar to Arthur, Collins

Ball, M. Quest for a hit and myth, The Weekend Australian, June 26-27, 2004

Barber, C. & Pykitt, D. 1997 Journey to Avalon, The Final Discovery of King Arthur, Weiser Books

Briggs, P. 1922 King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table.

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.126390

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phillis_Briggs

http://raymondsheppard.blogspot.com/2015/07/

Bromwich, R., Jarman, A.O.H. and Roberts, B.F. 1995 The Arthur of the Welsh: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval Welsh Literature, University of Wales Press

Day, D. 1995 The Search for King Arthur, Facts on File

Feerick, J. 2021

https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/was-king-arthur-a-real-person

Finke, L.A. and Shichtman, M.B. 2004 King Arthur and the Myth of History, University Press

Geoffrrey of Monmouth 2015 The History of the Kings of Britain, Penguin

Green, T. 2008 Concepts of Arthur, Tempus Publishing

Hibbert, C. 1970 The Search for King Arthur, Cassel

Higham, N.J. 2018 King Arthur The Making of a Legend, Yale University Press

Jones, W.L. 1914 King Arthur in History and Legend, Cambridge University Press

Johnson, P. 1975 The Offshore Islanders, Penguin

Lacy, N.J. 1993 Lancelot-Grail: The Old French Arthurian Vulgate and Post-Vulgate in Translation, Routledge

MacCann, R. 2018 King Arthur's Voyage to the Otherworld: Was Arthur Killed in America? Imperator Press

Matthews, J. 2004 King Arthur: Dark Age Warrior And Mythic Hero, Carlton Books

Lupack, A. 2007 The Oxford Guide to Arthurian Literature and Legend, OUP Oxford

Phillips, G. 2016 The Lost Tomb of King Arthur: The Search for Camelot and the Isle of Avalon, Bear & Company

Richards, P.D. and English, F.W. 1985 Out of the Dark A History of Medieval Europe, Thomas Nelson

The Modern World Encyclopaedia, Volume I, A to Bed, 1935, Home Entertainment Library

Websites:

https://britannia.com/biography/Nennius

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Annales_Cambriae

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Camlann

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cataphract

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chretein_de_Troyes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/de_Excidio_et_Conquestu_

Britanniae

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fagan_(saint)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galahad

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gildas

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historicity_of_King_Arthur

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/King_Arthur

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knights_of_the_Round_Table#...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lancelot-Grail

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_works_based_on/Arthurian_legends

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merlin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Post-Vulgate_Cycle

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Riothamus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Malory

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tintagel_Castle

https://folklore.culture.narkive.com/aL8qARAP/knights-of-the-round-table

https://guides.mysapl.org/c.php?g=485262&p=3698375

https://shepherd.com/best-books/the-origins-of-king-arthur

https://www.goodreads.com/list/show/4219.Best_Arthurian_Non_Fiction

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/610

https://www.livescience.com/28992-camelot

https://www.scribd.com/document/186767327/The-Welsh-Triads#

The Post-Vulgate Cycle (c.1230), a shorter re-write of the Vulgate Cycle, sidelines the Lancelot-Guinevere love entanglement and devotes more space to the Quest for the Holy Grail.

In the 15th century Le Morte d'Arthur (The Death of Arthur) by Sir Thomas Malory (c.1400-1470) drew heavily on the French Vulgate cycles and retold the entire legend in a single work intended to be comprehensive and authoritative. The Death of Arthur was one of the first books published by English printer William Caxton in 1485. Therefore in England and its colonies the Arthurian legends are best known from Malory's book. Malory got the date approximately correct, the 5th century, but the society he describes is 15th century. Malory's work in turn influenced Alfred Tennyson, T.H. White, John Steinbeck, Mark Twain and others who reinterpreted the legends. Malory's Arthur is what most subsequent English Arthur-novels (including Briggs 1922) and 20th century Arthur-movies are adapted from.

Briggs calls Lancelot "Launcelot", Tristan "Tristram", and does not identify Mordred as Arthur's son nor Galahad as Launcelot's son besides other differences.

MYTH

A large literature about Arthur's knights accrued over a period of centuries in Wales, England and France, the stories inconsistent with one another, and virtually all of it myth.

Consider the number of knights. Wikipedia says:

|

The number of the

Knights of the Round Table (including King Arthur) and their names vary

greatly between the versions published by different writers. The figure

may range from a dozen to as many as 1,600, the latter claimed by

Layamon. Most commonly, there are between 100 and 300 seats at the

table, often with one seat usually permanently empty… In many versions

there are over 100 members, as with 140 according to Thomas Malory (150

in Caxton's version) and Hartmann von Aue. Some sources state much

smaller numbers, such as 13 in the Didot Perceval, 50 in the Prose

Merlin (the prose expansion Vulgate Merlin has 250), and 60 in the

count by Jean d'Outremeuse. Others state higher numbers, as with 366 in

both Perlesvaus and the Chevaliers as deus espees.

|

The same Wikipedia page lists by name 57 "notable knights", and another 78 "less prominent knights" mentioned in the "Winchester Manuscript of Le Morte d'Arthur". Several names are names of real 15th century knights but don't appear in earlier historical manuscripts.

Briggs' novel mentions about 25 knights by name but: "One hundred and fifty knights can sit about it [the Round Table] any one time..." Two successive seats to one side of Launcelot remained free. After Percivale and Galahad arrived: "they sat at supper that night, with all the five score and fifty sieges [seats] filled..." (p. 132)

HISTORICAL SETTING

When the Romans departed around 410 CE Picts and Scots soon raided all over Celtic Britain.

A ruler in south England, requested the Jutes, a Germanic tribe in Denmark, for assistance. They assisted, but then stayed, and proceeded to subjugate the native British. Germanic tribes — Old Saxons, Angles and Jutes — arrived in force and plundered, enslaved and slaughtered.

The invaders preferred to build new communities in cleared forest areas and the Roman towns declined.

Britain's many warlords and petty kingdoms acknowledged one or a few powerful rulers as a "Vortigern" or overlord. One overlord was Ambrosius Aurelianus, a man with Christian beliefs and Roman background. Two German brothers, Hengist and Horsa, may have served him as mercenaries before turning against him.

Ambrosius' son born about 475 CE was Artorius, a Roman name derived from the family's allegiance to Rome. We see a possible derivation of "Arthur" from "Artorius". However, in the Arthurian legend Arthur's father is not named Ambrosius but Uther Pendragon.

Around 500 CE Saxon incursions became a mass migration. They came in boats, similar to the future Viking-boats, about 20 metres long, powered by rowing.

When Ambrosius died Artorius fought successful battles against Picts and Scots in the north and Saxons in southern England. The culmination was the battle of Badon Hill in 516 CE in which Artorius demolished a Saxon army according to the writer Nennius.

Briggs doesn't mention Badon Hill, instead describes an invasion of Flanders by Arthur with 62,000 men, where he defeats Lucius the Roman Emperor. (pp 37-42)

...tens

and tens of thousands fell upon the blood-soaked field. The flower of

Roman knighthood died

that day. The Sultan of Syria was among the dead, also the kings of Egypt and Ethiopia, seventeen

other lesser kings and sixty senators of Rome. (p. 42)

that day. The Sultan of Syria was among the dead, also the kings of Egypt and Ethiopia, seventeen

other lesser kings and sixty senators of Rome. (p. 42)

Briggs describes preparation for the battle: "The bowmen went into the fields and set up their targets and they shot from sunrise to star-rise till the meanest of them could shoot a second arrow upon a first and split it from feather to head." (p. 39) The Mythbusters (Episode 36) tried to replicate such splitting of arrows and found it impossible with solid wood arrows: "Because the second arrow will follow the grain, which will lead to the side before it makes it to the end." Success has only occurred, still extremely rarely, when the first arrow was made of hollow bamboo or modern carbon fibre. This is an incidental example of how myth gets built upon previous myth.

The "great battle" itself is also fantasy. In the 6th century neither Rome nor the British had the sort of military power and political influence described.

The Baden Hill battle in 516 CE, if it happened — some scholars now query that too — was not a battle of armour-clad knights on horses or even of cataphracts. Saxons might ride to a battle area on horses but fought on foot with swords, spears and battle axes and protected by a helmet, shield and leather jacket.

Artorius' victories resulted in Saxons vacating south-west England and established him as the dominant king. Twenty years later, round 537 CE, his kingdom collapsed in civil war. The writer Gildas describes this period but writes more propaganda than history and mentions neither Arthur nor Artorius by name.

Arthur died, according to tradition, after a long separation from Guinevere, when he tried to visit her at Glastonbury where she lived in a convent. In Briggs' book Arthur and Mordred kill each other in a final battle.

In the mid 6th century the Arthurian or Artorius peace, if it happened, was gone. The Anglo-Saxons dominated England and set up seven kingdoms, the Heptarchy:

• West Saxons in Wessex

• South Saxons in Sussex

• East Saxons in Essex

• Jutes in Kent

• Angles in Northumbria

• East Angles in East Anglia

• Middle Angles in Mercia

• South Saxons in Sussex

• East Saxons in Essex

• Jutes in Kent

• Angles in Northumbria

• East Angles in East Anglia

• Middle Angles in Mercia

These kingdoms fought each other until around 850 CE the seven became three. At this time came the reign of Alfred the Great, King of Wessex, and the Viking invasions.

The subjugated British in the 7th to 9th centuries perhaps got comfort from legends based on Artorius, now attributed to Arthur, to which Alfred's struggles perhaps provided further material.

THE GREATEST FIGHTER

Briggs writes:

All the knights strove

to be the best, and they so improved in arms and honour that they were

soon the finest body of men known in any age. But far above them all

was Sir Launcelot. Gentle and brave, handsome and chivalrous, he was a

pattern of true knighthood, and no one was ever found who could

overcome him in combat except by enchantment or deceit. (p. 43)

He [Launcelot] set out with all speed, riding straight for Pendragon Castle, for he was afraid of nothing. As he neared the place, the six knights came out as before, and as before they all prepared to set on him at once in most unknightly fashion. But they had other metal against them this time; the greatest fighter in the world was charging down upon them. (p. 117)

He [Launcelot] set out with all speed, riding straight for Pendragon Castle, for he was afraid of nothing. As he neared the place, the six knights came out as before, and as before they all prepared to set on him at once in most unknightly fashion. But they had other metal against them this time; the greatest fighter in the world was charging down upon them. (p. 117)

Sir Tristram of Ireland was his equal:

At his last battle be

fought with Sir Launcelot and that was indeed a great fight. The two

were so

well matched that neither could gain the advantage… (p. 95)

well matched that neither could gain the advantage… (p. 95)

And, later, Galahad: "No man could stand against him when the jousting began, save only two, Sir Launcelot and Sir Percivale." (p. 132)

Percivale arrived in Camelot after Tristram returned to Ireland and got the second of the two vacant seats next to Launcelot. (p. 122)

TINTAGEL

Camelot appears in detail in the Vulgate Cycle, the c.1220 French compilation mentioned above. Geoffrey of Monmouth implied Tintagel, on the Cornwall coast, was Camelot and Arthur its king; and Alfred Tennyson advocates Tintagel in his poem Idylls of the King.

Archaeologists have excavated the remains of large 6th century buildings at Tintagel and unearthed high-standard imported pottery, indicating the inhabitants were upper-class. Skeletons dug up in southern England have undergone genetic analysis. The findings suggest that in the sixth century Saxons dominated eastern England and traded with northern Europe. The British dominated the west and traded with the Byzantine Empire.

The two areas were apparently at peace for a time when Saxon arrival was by immigration not invasion. Tintagel was the main trading centre in the west and controlled locally-mined tin which was in demand in Europe to make bronze. Tintagel was prosperous but whether its king was Arthur is unconfirmed.

The "Arthur stone", discovered in 1998 in the ruins of Tintagel Castle, created a stir and featured in a TV documentary, but proved irrelevant.

OTHER NAMES

During the 12th century, Arthur's character began to be marginalised by stories about Tristan, Lancelot, Guinevere, Percival, Galahad, Gawain, the Holy Grail, Merlin, and others.

The Welsh and French stories include hundreds of characters in thousands of pages, all even less historical than Arthur.

Arthur himself changes significantly:

In both the earliest

materials and Geoffrey he is a great and ferocious warrior, who laughs

as he personally slaughters witches and giants and takes a leading role

in all military campaigns, whereas in the continental romances he

becomes the … "do-nothing king", whose inactivity and acquiescence

constituted a central flaw in his otherwise ideal society.

The tales are largely of courtly love and knightly adventures with Arthur's reign as background. Lancelot, Guinevere and Galahad became important characters, Merlin's role greatly expands, Mordred is born from incest between Arthur and his sister, and Camelot becomes Arthur's capital.

Galahad was the illegitimate son of Lancelot and Lady Elaine. Elaine's father, King Pelles, purchased a magic ring from an "enchantress" that makes Elaine look like Guinevere and fools Lancelot into spending the night with her. Galahad first appears in the fourth book of the Vulgate Cycle and continues in the Post-Vulgate Cycle and Malory's The Death of Arthur. Galahad is raised by a great aunt in a nunnery. Arthur, upon realizing Galahad's greatness, leads him to a river on which floats a stone with a magic sword embedded, inscribed: "Never shall man take me hence but only … the best knight of the world." Galahad becomes renowned for his gallantry and purity. He banishes demons, performs miracles, and finds the Holy Grail.

A huge amount of literature is about Merlin featuring many stories inconsistent with each other. His traditional biography casts him as sired by an incubus or lustful demon from whom he inherits supernatural powers including prophecy and shape-shifting. Merlin was created by Geoffrey of Monmouth probably as a composite figure based on previous kings, madmen, seers and prophets. Merlin became popular in Wales and was later rounded out by writers in France. One manuscript has him as the builder, helped by giants, of Stonehenge.

The popularity of Arthur stories gradually declined after 1634 when reprinting of Malory's The Death of Arthur stopped. Interest reawakened in the 19th century after its reprinting recommenced in 1816, and William Wordsworth wrote The Egyptian Maid (1835), and Alfred Tennyson's poem The Lady of Shallot (1832) gave an enchanting description of Camelot.

PHYLLIS BRIGGS

In the 19th-20th centuries came many retellings of Arthur in novels, most of them abridged or adapted from Mallory, including:

1862 J.T. Knowles, The Legends of King Arthur and His Knights

1880 S. Lainier, The Boy's King Arthur

1898 C.H. Hansen, Stories of the Days of King Arthur

1903 H. Pyle, The Story of King Arthur and His Knights

1903 M.L. Radford, King Arthur and His knights

1917 A.W. Pollard, The Romance of King Arthur

1918 S.E. Lowe, In the Court of King Arthur

1926 J. Erskine, Galahad: Enough of His Life to Explain His Reputation

1953 R.L. Green, King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table

1958 T.H. White, The Once and Future King

1982 M.Z. Bradley, The Mists of Avalon

1880 S. Lainier, The Boy's King Arthur

1898 C.H. Hansen, Stories of the Days of King Arthur

1903 H. Pyle, The Story of King Arthur and His Knights

1903 M.L. Radford, King Arthur and His knights

1917 A.W. Pollard, The Romance of King Arthur

1918 S.E. Lowe, In the Court of King Arthur

1926 J. Erskine, Galahad: Enough of His Life to Explain His Reputation

1953 R.L. Green, King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table

1958 T.H. White, The Once and Future King

1982 M.Z. Bradley, The Mists of Avalon

King Arthur by British novelist Phyllis Briggs (1904-1981) achieved many editions by different publishers in the 1950s and beyond. The existence of the 1922 version when she would have been only 18 is an anomaly.

Briggs includes miracle-stories like the names of knights appearing miraculously on their round-table seats, and the "lady of the lake", but sanitises out most of the medieval stories of the supernatural and magic and monsters.

COMMENTS

There were British leaders who defended Britain against Saxon invaders around 500 CE. But Arthur is not mentioned in any surviving manuscript written between 400 and 820.

The Ecclesiastical History of the English People (731CE) by Anglo-Saxon historian the Venerable Bede (673-735) mentions the Badon battle but not Arthur.

Archaeology has not discovered the Round Table, Excalibur, the Holy Grail, or 6th-century plate-armour; or identified Camelot, Arthur's castle, or Avalon (the island with Arthur's tomb); or found his other tomb in the ruins of Glastonbury Abbey. Nothing.

To a sparse history of a violent 6th century England and a local hero name Artorius, story-tellers and poets, beginning three centuries later, added ever more characters, adventures, miracles and supernatural events.

And that's what we have — imaginative romances and miracle-stories, mutually inconsistent, authored as entertainment which, by shear repetition, got accepted as history. The most useless presentations are the movies since these re-adapt mythical adventures themselves based on earlier myth. Guinevere, clad in only a leather, two-piece, beach costume, certainly did not sword-fight in battles as does Keira Knightley in Arthur (2004).

In the 20th century, historians such as John Morris in The Age of Arthur (1973) still regarded Arthur's reign as probable. Others have tried to connect Arthur with Scotland, or to legends originating in the Ural Mountains. The modern fiction and research on Arthur amounts to a vast literature exceeding the Medieval material. But most historians now regard Arthur as unhistorical, no more factual than Galahad, Lancelot, Merlin or the Lady of the Lake. Some regard even Aurelianus, Artorius and Hengist and Horsa as myth — concluding that the ancient historians who mention them relied on hearsay.

Feerick (2021) quotes British archaeologist Nowell Myres (1902-1989) who devoted 50 years to the search for Arthur: "no figure on the borderline of history and mythology has wasted more of the historian's time."

To prove that something never existed can be difficult because in some unexplored corner it perhaps did. Absence of evidence is not always evidence of absence. On present evidence, however, Arthur and his knights are no more historical than Spiderman or Wonder Woman.

REFERENCES / BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Ardrey, A. 2013 Finding Arthur: The Truth Behind the Legend of the Once and Future King, Duckworth

Ashe, G. 1906 From Caesar to Arthur, Collins

Ball, M. Quest for a hit and myth, The Weekend Australian, June 26-27, 2004

Barber, C. & Pykitt, D. 1997 Journey to Avalon, The Final Discovery of King Arthur, Weiser Books

Briggs, P. 1922 King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table.

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.126390

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phillis_Briggs

http://raymondsheppard.blogspot.com/2015/07/

Bromwich, R., Jarman, A.O.H. and Roberts, B.F. 1995 The Arthur of the Welsh: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval Welsh Literature, University of Wales Press

Day, D. 1995 The Search for King Arthur, Facts on File

Feerick, J. 2021

https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/was-king-arthur-a-real-person

Finke, L.A. and Shichtman, M.B. 2004 King Arthur and the Myth of History, University Press

Geoffrrey of Monmouth 2015 The History of the Kings of Britain, Penguin

Green, T. 2008 Concepts of Arthur, Tempus Publishing

Hibbert, C. 1970 The Search for King Arthur, Cassel

Higham, N.J. 2018 King Arthur The Making of a Legend, Yale University Press

Jones, W.L. 1914 King Arthur in History and Legend, Cambridge University Press

Johnson, P. 1975 The Offshore Islanders, Penguin

Lacy, N.J. 1993 Lancelot-Grail: The Old French Arthurian Vulgate and Post-Vulgate in Translation, Routledge

MacCann, R. 2018 King Arthur's Voyage to the Otherworld: Was Arthur Killed in America? Imperator Press

Matthews, J. 2004 King Arthur: Dark Age Warrior And Mythic Hero, Carlton Books

Lupack, A. 2007 The Oxford Guide to Arthurian Literature and Legend, OUP Oxford

Phillips, G. 2016 The Lost Tomb of King Arthur: The Search for Camelot and the Isle of Avalon, Bear & Company

Richards, P.D. and English, F.W. 1985 Out of the Dark A History of Medieval Europe, Thomas Nelson

The Modern World Encyclopaedia, Volume I, A to Bed, 1935, Home Entertainment Library

Websites:

https://britannia.com/biography/Nennius

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Annales_Cambriae

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Camlann

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cataphract

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chretein_de_Troyes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/de_Excidio_et_Conquestu_

Britanniae

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fagan_(saint)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galahad

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gildas

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historicity_of_King_Arthur

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/King_Arthur

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knights_of_the_Round_Table#...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lancelot-Grail

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_works_based_on/Arthurian_legends

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merlin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Post-Vulgate_Cycle

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Riothamus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Malory

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tintagel_Castle

https://folklore.culture.narkive.com/aL8qARAP/knights-of-the-round-table

https://guides.mysapl.org/c.php?g=485262&p=3698375

https://shepherd.com/best-books/the-origins-of-king-arthur

https://www.goodreads.com/list/show/4219.Best_Arthurian_Non_Fiction

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/610

https://www.livescience.com/28992-camelot

https://www.scribd.com/document/186767327/The-Welsh-Triads#

(BS)